Edit 01/02/2021: Changed to reflect that this code now exists as a separate package

Note: This tutorial uses the scivana-python package, and is aimed for users of https://alexjbinnie.itch.io/scivana

The shared state is a fundamental part of how Narupa operates. In essence, it is a dictionary containing data which is synchronised between the server and each user. All of these endpoints have a complete copy of the shared state.

The scivana-python package provides methods for interacting with the shared state. This package can be installed via the following command:

python -m pip install --index-url https://test.pypi.org/simple/ --no-deps scivana-python-alexjbinnie

The shared state can then be accessed by the methods of the SharedState class, namely calling SharedState.from_client on a client (any class derived from NarupaImdClient) or SharedState.from_server on a server (any class derived from NarupaApplicationServer).

The object returned from this is an instance of SharedStateDictionaryView. To understand the python API for shared states, we must understand the concept of views, references, collections, and snapshots:

Views & References

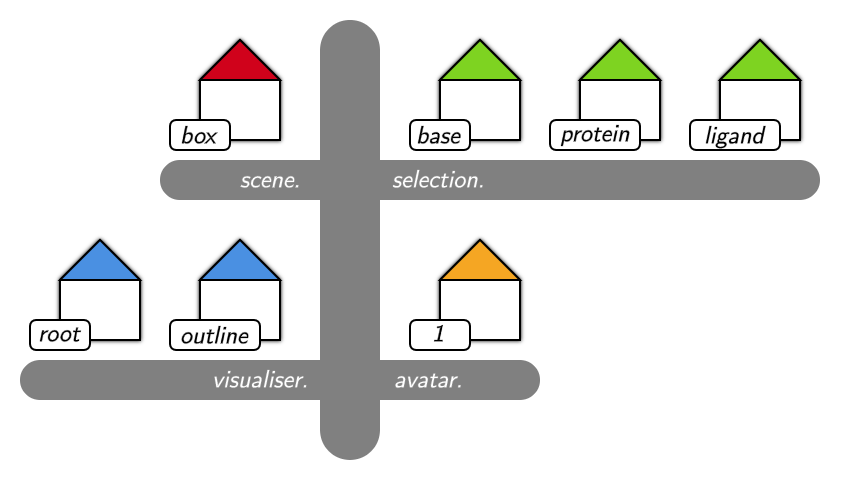

Each item in the shared state has a key which identifies it, such as "scene.box" or "selection.protein". More specifically, it identifies ‘where’ it is. If I want to know the current value of something, I look up the key in the shared state and see if a value is present and what is is.

This means the key acts like an address. Imagine the shared state like a town with each value living inside a little house. Each key is the house’s address, and we could consider a group of keys that start with the same prefix (such as selection.base, selection.protein, etc.) as lying on the same street.

When we lookup a key in the dictionary, it doesn’t actually return the value. Instead, it returns a reference (specifically, a SharedStateReference) to that specific key. Imagine a reference as being something that represents ‘what this key points to in this shared state‘. In our address analogy, by calling shared_state["selection.base"] we have specified which town this address can be found.

Why is it useful to return a reference? Well, imagine this case:

value = shared_state["some.key"]

# ...at some point the value in the shared state is changed

# now, our value no longer reflects what the current value is. If we want the current value, we'd have to look it up again using the key

new_value = shared_state["some.key"]

By using references instead, we enable a workflow that looks like this:

reference = shared_state["some.key"]

value = reference.snapshot()

# ...at some point the value in the shared state is changed

# our reference doesn't contain the value, it just says where to find it! we call snapshot() to get the current value

# note we don't need to keep track of the shared state or key, both are encapsulated in the reference

new_value = reference.snapshot()

Our references are basically the addresses of our little houses. Think of the key as being something like ‘42 High Street‘. This alone doesn’t identify an exact house, so we need to ask for this key at a specific shared state (here representing a town).

By calling the snapshot() function of a reference, we are visiting and finding out who lives in the house at that specific point in time. This value won’t be updated, so if I call snapshot() at some later date, someone else might have moved in!

It is possible to obtain a reference to any address, even to those that don’t exist yet. If you try to call reference.snapshot() on a reference when the shared state doesn’t actually contain that key, a KeyError is thrown. If you would like to avoid this, it is possible to check that a reference actually has a value by checking reference.has_value is true before calling reference.snapshot().

Collections

I mentioned before that we can group together a set of keys in the shared state by a common prefix, such as "selection.". This corresponds to a street in our picture of the shared state as a town. In the same way that shared_state is a view of the whole town, a SharedStateCollectionView is a view of just the keys that begin with a given prefix. We can create a collection view using the collection() command:

# get a collection view of all keys that begin with 'selection.'

collection = shared_state.collection('selection.')

Note that there are several built in shortcuts added directly to the server and client classes from which we access the shared state. However, these just call collection() behind the scenes.

# get the collection of all selections on the server

selections = server.selections

# get the collection of all visualisers on the client

visualisations = client.visualisations

What is the point of these collection views? Firstly, any function you use with them that involves a key automatically resolves the key by adding the prefix if it is not present. For example:

# Creates a selection with the key 'selection.abc'

selections["abc"] = ParticleSelection(display_name="Pair", particle_ids=[0, 2])

# Delete the visualisation with the key 'visualiser.root'

del visualisations["root"]

This key resolution helps keep code simpler, so you do not have to remember that exact prefixes for common collections such as selections and visualisations.

Secondly, collections can have a type associated with them. This means, when dealing with selections for example, any snapshots are actually translated into a ParticleSelection, even though they are stored as dictionaries. This helps in writing strongly typed code involving the shared state.

Changing Values

I’ve talked about how to access values by using the snapshot() function (snapshots can be taken of individual references, collections or even the entire shared state dictionary). But how do you add new values to the shared state?

For editing the shared state directly, we can either use item assignment (the more pythonic way) or the corresponding shared_state.set() command:

# Add the value 2.4 to the shared state under the key 'some.key'

shared_state["some.key"] = 2.4

# Set the key 'ambient_occlusion' to false

shared_state.set("scene.ambient_occlusion, False)

Note that this adds a new value if the key wasn’t present, but overrides if there was an existing value already.

For collections, we also have a shortcut for when we don’t care what the key is:

# Add a selection with a randomly assigned key. add() returns a reference, so we should keep a hold of it in case we want to modify this selection later

selection = selections.add(ParticleSelection(display_name="Base", particle_ids=[0, 4]))

# can also call add with keyword arguments because selections knows everything in it is a ParticleSelection

selection = selections.add(display_name="Base", particle_ids=[0, 4])

For changing values, set has you covered. But when dealing with values that are themselves dictionaries (such as selections, visualisations and most other interesting things you’d be dealing with), you may end up with code looking like:

# Get a copy of the current value

value = reference.snapshot()

# Change one or two fields of that copy

value["some_field"] = 91

# Set this copy as the new value

reference.set(value)

To mitigate this, there are two options: using update() or modify(). Using update() performs the above piece of code, using the keyword arguments as the changes you’d like to apply. The above three lines can be condensed to

# Update the value this reference points to so that 'some_field' is 91

reference.update(some_field=91)

Note this only works if the current value both exists and supports assignment (like value['some_field'] = 91). Therefore, this works for both dictionary values and values which are selections, visualisations etc.

If we’re changing several fields, we may prefer to use modify() instead. This returns the current value in a context block, and at the end the modified value is automatically inserted back into the shared state:

with reference.modify() as value:

# value is a copy of what is currently in the dictionary

value['some_field'] = 91

# when the with block is finished, value is copied back into the shared state

Deleting Values

Deleting values is simple, and can be done either at the shared state or reference level:

# remove the value with the key 'some.key' from the shared state

del shared_state["some.key"]

# remove the value which a reference points to

reference.remove()

Bringing it together

Here are some examples of using the shared state API. Here, client and server have already been setup and the client has connected to the server.

# Use a client to add a visualisation that applies to everything, and renders it all in liquorice

client.visualisations.add(display_name="Base", visualiser="liquorice", layer=0, priority=0)

# On the server, add a selection for a a few particles and draw them as hyperballs

# Deliberately choose the key 'selection.hyperballs' by using set instead of add

selection = server.selections.set('hyperballs', display_name="Selection", particle_ids=[44, 45, 46, 47])

# Note that this visualisation needs to know what selection to apply to, so we access the .key property of the reference

selection_vis = server.visualisations.add(display_name="Selection", selection=selection.key, visualiser="hyperballs", layer=0, priority=1)

# At some later point, the client wants to modify the selection with the key 'selection.hyperballs'

client.selections.update('hyperballs', particle_ids=[43, 44, 45])

# The server decides that it doesn't want to draw the selection anymore

selection_vis.remove()

# The client decides to clear all visualisations, resetting the shared state back to being empty

client.visualisations.clear()